Alexander Charles Davis

Private 568

Alexander Charles Davis | ||

| North Somerset Yeomanry, 'A' Squadron Private 568 | ||

| Died 17th November 1914 |

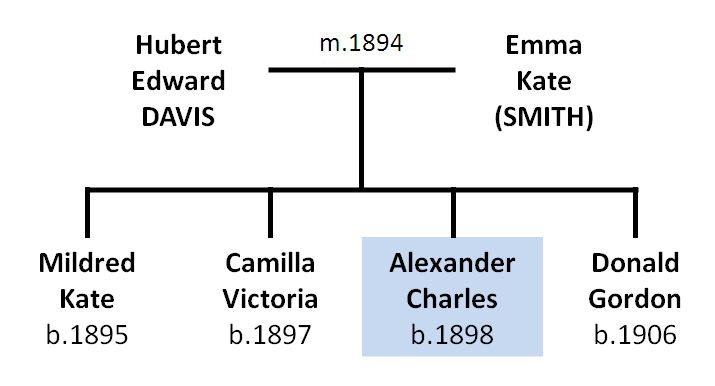

Alexander Davis' Parents | ||

| Alexander Charles Davis was the third child born to Hubert and Emma Davis. | ||

|

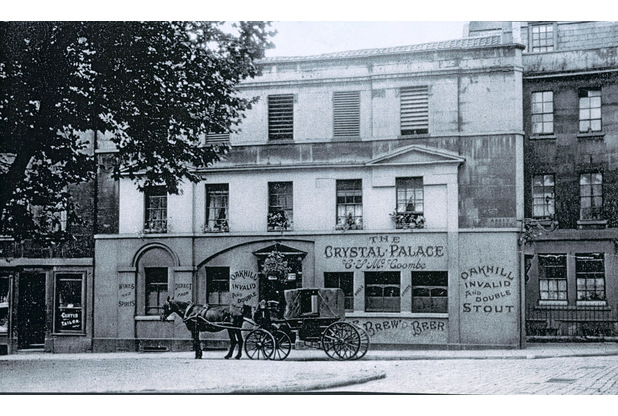

Emma Smith Alexander’s mother, Emma Smith, grew up in central Bath, first in a row of cottages next to the Canal Bridge in Widcombe and later in a cottage at the rear of number 10 Abbey Green. This is now – as it was then – the Crystal Palace public house. The cottage to the rear is no longer there. |

| ||

|

A 19th century postcard view of the Crystal Palace public house on Abbey Green, where Alexander Davis’ mother

lived in a cottage to the rear of the premises in the 1880s. |

|

Emma’s father was listed as a maker of harp strings and her

mother was a needlewoman. In addition to the ten family members listed as

living in this cottage, three other siblings had died at (or soon after) birth.

She would have remembered the twins that died when she was eight years old.

Living as one of ten family members in a ‘cottage’ would have made for quite

cramped living conditions. By 1891, Emma’s elder sister Winnie had married the landlord of the Crystal Palace, William McCoombe (23 years her senior!), whose first wife had died in 1884. Emma subsequently lived in the pub itself; her parents and other siblings were still living in the cottage to the rear. Hubert Davis Alexander's father was born in Barnwood, in the northern part of the city of Gloucester.

Hubert’s father in turn was a master bookbinder and census returns show Hubert

living in Wotton-under-Edge in 1871 (age 4) and in Upton St. Leonards in 1881 (age

14). By 1891, however, he had moved to Bath and was living at 1, Westgate

Buildings, practising as a hairdresser and tobacconist. Number 1 Westgate

Buildings was not quite on the end of the row (it was roughly in the position

currently occupied by the southern part of Pizza Hut), but abutted the

buildings called ‘Bush Corner’, the premises of Sidney W Bush, at Westgate

Place, which faced north across towards the Seven Dials Inn. |

| ||

|

This photograph shows 1 Westgate Buildings, where Hubert

Davis had his shop, seen here with a bicycle leaned against the shop-front.

Today Pizza Hut is on this site. [Image: Bath In Time] |

| Alexander’s parents married in 1894 at St James’ Church in Bath. This church stood at the top of Southgate Street (roughly where Marks & Spencer now stands), but was demolished in the late 1950s after having been destroyed by German bombing in April 1942. |

The Davis Family |

|

|

Throughout the 1890s, the Davis family lived at 1 Westgate

Buildings, with Mildred & Camilla born in 1895 & 1897 respectively. Alexander himself was born in 1898 and

the family soon moved into more spacious accommodation at 10 Victoria Buildings

(Lower Bristol Road, near the bottom of Brougham Hayes). |

| ||

|

10 Victoria Buildings, Lower Bristol Road. Home to the Davis family

1900-1910 |

|

Hubert Davis still had his barber shop in Westgate Buildings and it

was in regard to his shop that he featured in the newspaper in 1908: |

|

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette - Thursday 23 July 1908 ALLEGED OBSCENE READING MATTER. PROSECUTION IN BATH. At the Bath City Police Court, on Thursday, before Major C. H. Simpson (in the chair), Messrs. J. W. Knight, E. Lewis, and F. Young, Herbert Edward Davis, a hairdresser, of 1, Westgate Buildings, was charged on a warrant with exhibiting to the public view in his shop window, on July 14th, certain printed matter of an obscene character. Mr. J. S. Carpenter appeared for the prisoner, who pleaded not guilty. Detective Inspector Burge stated that the previous afternoon he visited the prisoner's shop in company with Detective Marshfield. He took the card (produced) from the shop window near the glass. Witness showed the prisoner the card and told him that he held warrant for his arrest. Prisoner replied, “I didn't think there was anything wrong in it." Witness told him that he was going search his shop, and prisoner replied, "You won't find anything else here. I have not sold any. This is the only one I've got. I had it given me by a gentleman." The prisoner said several times that he had not had any cards similar to those found in the window. Witness then searched the shop, and found no cards of a similar character to that taken from the window on the prisoner's premises. Witness then removed the prisoner to the Central Police Station. Replying to Mr. Carpenter, witness said that he did not think that the card had fallen into its position in the window accidentally. He thought that it had been put there for people to read it. Mr. Carpenter suggested that no one would see the card unless they went into the shop, but witness explained that this shop was situated in a recess, and that the card in its position could be easily seen. Witness admitted that he had known the prisoner for practically 17 years, and no charge of this character had been before brought against him. D.C. Marshfield gave corroborative evidence, and admitted in cross-examination by Mr. Carpenter that he had known the prisoner for eight or nine years, and had heard of no such charge as the present being brought against him. For the defence, Mr. Carpenter submitted that in point of law the document in question was not obscene. It was one which could read in two ways, and its ex-facie reading was a perfectly innocent one. He quoted a decision to show that when a document could be read in two ways it was not for the magistrates to put the wrong interpretation upon it. The prisoner had thrown the card away, but his boy had picked it up and put it in the window for a joke. Prisoner was willing to take the responsibility for his employee's action. The Chairman intimated that the magistrates considered that the document found in the prisoner's shop was of an obscene nature. Mr. Carpenter then again addressed the magistrates, and suggested that the case might be dismissed upon payment of costs and the prisoner giving an undertaking that nothing of objectionable character should again appear in his shop. The Chairman said that but for the evidence the magistrates would have taken a more serious view of the offence of which he had been guilty. He would be fined 20s and costs, or 14 days. |

|

Sadly, the exact nature of the ‘double entendre’ does not

survive! The family remained living at Victoria Buildings until 1908,

when they took up residence at 23 Westgate Street (now the site of ‘Komedia’

and of the Beau Nash cinema before that), just a few yards from Hubert’s shop.

The 1911 census shows that the family was playing host to Alexander’s cousins Elsie & Charles on census night. Given that children attended school between the ages of about 5-12, we can deduce that Alexander would have been at South Twerton School between circa 1903 and 1908 and would probably have completed his schooling (after 1908) at a city centre school such as the Bathforum School. Based on the family’s residency in Victoria Buildings, it is actually a mystery why Alexander attended South Twerton at all, when East Twerton School (now Oldfield Park Infants) was much closer tp his home. There was however constant adjustment made to the catchment areas within Twerton parish to ensure class sizes matched school building capacity. We do not know what Alexander did between school and the joining the military in 1914.Shortly before the war, the family moved home (and father Hubert’s business) to 82 Lower Bristol Road, in the row of shops adjacent to St James Cemetery. He would have been a well-known figure among men-folk in the city, as many hairdressers are today, and would have had his finger on the pulse of everyday goings-on. When he died in the 1930s, the newspaper item called him “The Don” – reason unknown! |

Alexander Davis in WW1 | ||

North Somerset YeomanryAlexander

served with the North Somerset Yeomanry, having joined in the early summer of

1914, prior to the outbreak of war. The NSY was a small unit with just three

battalions when war broke out in August 1914.

‘A’ Company was based in Bath and it is therefore very likely that Alexander served in this company. | ||

| ||

| A WW1-era badge of the Somerset Yeomanry with the Latin motto 'arma pacis fulcra', meaning 'armed strength for peace' |

|

The 1/1st Battalion was quickly mustered as part of the

immediate response to war; the Bath Weekly Chronicle & Gazette carried a

report on 15th August of the NSY’s departure for active service. Following an afternoon parade at their HQ at the Drill Hall,

Lower Bristol Rd (now the site of the Holiday Inn at the bottom of Brougham

Hayes), which would have served as an opportunity to leave family and friends

with a positive mental image of the unit, they gathered at the Westmoreland goods

yard of the GWR (now the site of Pickfords and 'The Square') at 5pm, planning to leave at 6.50pm. They numbered 156 officers

and men and 175 horses. They eventually left at around 10.30pm after loading

the horses onto the trains. Although well-wishers had lined the route on the

Lower Bristol Road and Old Bridge, expecting them to march to the main station,

they boarded the train at Westmoreland and could only wave to onlookers from

the viaduct as the train moved through. So began the journey to the front. After 10 days at Winchester, the regiment proceeded to join the

1st South Western Mounted Brigade training camp at Kidbrooke

Park, just outside the village of Forest Row in Sussex before being mobilised. They sailed from Southampton to Le Havre on 2nd November, arriving on 3rd, and were under canvas just outside Le

Havre for 3 days. There followed a day’s train journey to St Omer and a 7-mile

walk to the small village of Esquerdes, where they rested and spent a few days

getting to grips with some trench digging practice. It was here that they

learned of their attachment to the 6th Cavalry Brigade. On 11th November, while parading for drill, they

received orders to march. With just three hours’ notice, they were mobilised

into the heart of the battle and began a 40-mile trek to Ypres. The First Battle of Ypres

The early stages of the war in France in September 1914 had

degenerated into a stalemate between entrenched positions around Aisne. With

strategic ground on either side up for grabs, a series of attempts of both

sides to outflank the other (northwards) led to what became as the ‘Race to the

Sea’. Ypres (now ‘Ieper’) in Belgium became a strategic city and the area

around the city saw some of the fiercest fighting at various points throughout

the war. The city itself was all but destroyed during the course of the war. The First Battle of Ypres took place in October &

November 1914. The North Somerset Yeomanry’s first taste of the war

The NSY completed its first trench duty in the area of Zillebeke, three miles to the SW of the city of Ypres. A letter back from the front from SSM W. Reeves of the 7th Hussars told of his experience of the NSY as they fought alongside his unit in the 6th Cavalry Brigade: |

|

“As you know, when we left England there was some idea that we should

not be sent up into the fighting line, and employed on more peaceful duties.

This idea was very quickly dispelled, for we had only been out a few days when

we were sent up into the very thickest part of the fighting. Our first real

introduction to the fighting was when a real "Jack Johnson," shell

which I believe weighs something like 800 lbs., came screaming over our heads,

and struck the ground within yards, smothering half the squadron with mud and

dirt, and causing large stones to fly in all directions. We then tied our

horses in a field, which appeared to have been favourite spot for the German

artillery, as there were five great holes in this particular field where the

shells had dropped. We had not been there very long before they began to drop

around us again, and one actually came so close that several of the men were

knocked down by the force of the explosion. That evening we formed to go into

the trenches, and a few moments after moving off a shell struck the exact spot

which the regiment had stood in mass, just a few moments too late to wipe out

half the regiment. We marched about four miles to the trenches, floundering

through mud up to our knees, and when we arrived we were told that we were not

required, so we marched back. We all turned in in a building for the night, but

it was obvious the Germans had got wind we were there, for their shells

continued to drop the whole night, and one eventually dropped near enough the

officers' quarters to smash every window in the place. Then we saddled and

cleared, and it seemed an act of Providence that, with the exception of Yerbury

and one man from ‘B’ Squadron slightly injured, we had no other casualties,

either to horses or men. “The following night we were ordered to take our turn of 48 hours'

trench duty, and on our arrival there three troops of 'A' Squadron were sent

into the firing or main trenches, and the remaining troop and the other two

squadrons were put in the supporting and reserve trenches. The night was

bitterly cold, but, with the exception of an occasional outburst of rifle fire,

passed fairly quietly. During the morning and well into the afternoon we were

subjected to a most terrific shell fire from the German artillery, and it is

utterly impossible to try and describe the helpless feeling one has when the

trench and having all sorts of shells banging and bursting overhead. I think we

must have had quite 200 shells at us during the afternoon, and when I tell you

that not a single man in the trench was hit, it will seem hardly credible. "We were due to relieved by ' B ' Squadron at about 6.30 p.m.

About 6.00 the Germans made a strong attack on our trenches, but we saw them

coming, and gave them something to go on with, but it took over an hour to

finally push them back and for us to get relieved. 'B' Squadron and the

remaining troop of ' A' Squadron then took positions in the main trench, while

the other three troops of 'A' squadron went back to the reserve trench. “During the night things were fairly quiet, but about 10.30 the next

morning the German guns began to shell our trenches for all they were worth.

This went on for, perhaps, a couple of hours, and soon after mid-day their

infantry attack commenced. They came along in hundreds, and our fellows simply

knocked them over in dozens, and again and again we drove them back. After a

time, as things were looking rather critical, word was sent back for the

remainder of 'A' to go up in support, which we did and we were then able to

hold them, and finally drive them back. "Our losses were heavy, but we have the satisfaction of knowing that we bore the brunt of the attack, and the finest troops in the world could not have stood their ground or been steadier under fire. There was never any suspicion of them giving way, and all the stories about our boys not being fit for service have been dispelled. "We had six killed in the Bath Squadron: Sergt. Bristowe. Sergt. Gooding, Corpl. George. Corpl. Adams, Pte. Harvey and Pte. Davis. I cannot stay to write more now, but whatever may be said we have the satisfaction of knowing we did our duty, and, if called upon, will do it again." |

|

The details of Sergeant Major Reeves’ report were

corroborated in many letters home from the front, quotations from which were

published in the Bath Chronicle & Weekly Gazette in the immediate aftermath

of this ‘baptism of fire’ for the North Somerset Yeomanry. |

Alexander Davis' Death | ||

| The North Somerset Yeomanry's unit diary for 17th November, the day of Alexander Davis’ death reads: | ||

|

Zillebeke A

determined attack was made at noon which was repulsed with heavy loss causing

the regiment many casualties including Capt Liebert who was killed. The attack

was renewed and Brig Gen Lord Cavan was now informed and asked for

reinforcements. He sent up 2 companies of Coldstream Gds who occupied the

reserve trenches at 3.30pm. Meanwhile the attack had been continued and Lt J S

Davey killed. 30 men of A Squadron were sent up under Capt R E English to

replace casualties. Later on the remainder of A Squadron under Maj G Lubbock

was sent up. The

enemy made another determined attack at dusk but was repulsed with heavy loss

making it unnecessary to call up the Coldstream Guards. The enemy sent up a

balloon at midday with flags attached and in the evening used magnesium light

to direct the attack. The relief of the trenches was carried out at 6.30pm by

the 2nd Life Guards in

the firing line and R[oyal] Horse Guards in reserve. C Squadron came under

heavy shell fire in the reserve trenches but did not occupy the front trenches. The

regiment marched dismounted to Ypres where it picked up its horses and returned

to its billets near Vlamertinghe. Casualties

- Capt F G C Liebert and Lt J S Davey killed. Capt S G Bates 7th Hussars (adjutant) and 2/Lt A N

Bailward wounded. NCOs and men killed 22. Wounded 39. Missing 3. Total

casualties 64. Out of these 59 were sustained by the 200 rifles in trenches at Zillebeke. The

weather has been bitterly cold the last few days and the horses suffered from

exposure. |

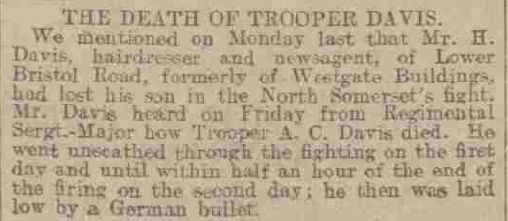

| The Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette of 28th November 1914 carried detailed reporting of the North Somerset Yeomanry’s experiences from numerous different sources. The report references ‘Trooper Davies’ (mis-spelt): |

|

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette - 28 November 1914 NORTH SOMERSETS’ BAPTISM OF FIRE 48 HOURS IN THE TRENCHES AT YPRES. 22 KILLED AND 43 WOUNDED GALLANT CONDUCT UNDER TERRIBLE SHELL FIRE 374 GERMANS FALL BEFORE THEM The North Somerset Yeomanry have undergone their baptism of fire at the front. The official story of their doings has yet to be told, but the details given in letters received from Belgium show that they have faced the grimmest of ordeals in the spirit of courage and doggedness characteristic of the West Countree and have covered themselves with undying glory. Such short and soldierly records as the men’s letters give are sufficient indication that when the full tale of their exploits comes to be written it will be worthy to rank with the records of the finest deeds in the annals of the British Army in any age or clime. For forty-eight hours our Yeomen occupied a position in the front line at Ypres, where the enemy had concentrated in a renewed attempt to break through to Calais. During this time they were incessantly bombarded, many of the shells which burst in their position being those terrible “Jack Johnsons” which weigh 900lbs and burst with awful effect. When the fight was over close upon 400 Germans lay dead in front of the trenches occupied by the North Somersets. Unhappily the Yeomen also sustained severe losses, 2 officers and 20 men being killed and 43 officers and men wounded. Bath and Weston-super-Mare suffered most severely, our own city having to mourn several gallant fellows who have laid down their lives on the altar of duty. In all six members of the Bath Squadron are dead, four of whom were residents in the city or its immediate neighbourhood. They are:

The officers killed are Capt. Liebert and Lieut. J S Davey. STATEMENT BY LIEUT-COLONEL GIBBS, M.P. ENEMY DRIVEN BACK THREE TIMES Lieut-Colonel G. A. Gibbs M.P. has supplied us with some particulars respecting the fight. Colonel Gibbs stated that the regiment spent two days and two nights in the trenches. The men behaved magnificently and no doubt the regiment had made a great name for themselves. As was bound to happen, there were casualties. ‘B’ Squadron (which is drawn from the northern part of the county, including Bristol and Weston-super-Mare) suffered the most. As far as he (Colonel Gibbs) could understand the worst fighting took place on the second day, when the North Somersets drove the enemy back three times during the battle. Comparatively speaking, ‘C’ Squadron suffered very slightly and only two men were wounded. The regiments was supported during the battle by the First and Second Battalions of the Coldstream Guards. On the second day, ‘B’ Squadron was in the front trenches. The Brigadier came afterwards and addressed the regiment in very complimentary terms and other regiments were very complimentary to them for the way they fought. “To sum up” said Col. Gibbs, “it was a very severe attack and the fact that the North Somerset Yeomanry repulsed it speaks for itself. For all the 48 hours the shell firing was very great, and probably few regiments have had such an introduction to fighting as they have had.” Lieut-Colonel Gibbs also informed our representative that the total casualties to the North Somersets killed and wounded are estimated to be 65. Two officers killed are Capt Liebert and Mr J. S. Davy, both of ‘B’ Squadron. Adjt. and Capt. Bates has been slightly wounded in the chin and Second-Lieutenant Bailward, who commands No 1 Troop of ‘H’ Squadron has been wounded in the head, though the injury is believed to be very slight. “NEVER A WAVER” GRAPHIC DESCRIPTION OF GERMAN ATTACKS Mr J. W. Edgell of Shepton Mallet has received a most interesting letter from Regimental Sergeant-Major Shakespeare, giving details of the fight. He says: “You will remember in my last letter I said the North Somersets were anxious to get at the throats of the Germans. We have had that time and have left a very distinct impression. I am proud to belong to this regiment, as in a recent engagement here we have done well. I will tell you all about it. “IT WAS BLAZING HELL” “On Sunday 15th November we received orders for 48 hours’ duty in the trenches. In the evening of that day we occupied our positions and during the night there was heavy firing by the German artillery. During the next day there was a big attack on our position, and the North Somersets answered the call and simply mowed them down. There was never a waver and the attack was repulsed. After that it was hell – simply awful, fierce, blazing hell. All sorts of shells came at the trenches, including ‘Black Marias’ and ‘Jack Johnsons’. This shell weighs about 800 pounds and makes a hole on bursting something like your lake in the park, high explosive shells and shrapnel. It was wicked, furious, and some of our poor fellows were simply blown to pieces. “A SECOND ATTACK” “During this hellish practice there was another fierce attack and another slaughter by our men. “It was magnificent to see how the North Somersets held their ground and some, in their eagerness, even got out of their trenches in an endeavour to meet the Hun before he got to our position. Dear Jack, at what a price! We had two officers and 20 men killed and two officers and 37 men wounded. I have just heard officially that there were counted 374 dead Germans in front of our position. PROUD TO BELONG TO SUCH A REGIMENT “I am not a Somerset man myself, and I again say I am proud and honoured to be allowed to belong to this regiment. We have been, and are being, congratulated by everyone from the General Officer Commanding downwards. SOME OF THE CASUALTIES [The letter then lists details of men local to Shepton Mallet]. Bath and Weston squadrons suffered the most, and the poor fellows which have gone under will be sadly missed. They were brave men and died nobly at the call of duty. MARVELLOUS ANYONE REMAINS ALIVE “It was simply marvellous how anyone could be left alive after the vicious shelling we had to undergo. I am writing this in a Belgian farm outhouse, and our fellows are in barns and what other cover can be obtained. It is very cold and miserable, but the men take it very well and they are quite cheerful. “We are being well provided for, as our food is plentiful and regular. We are now to be issued with warm clothing, that is wool lined coats and sweaters, also scarves and warm clothes.” ONE OF THREE BROTHERS WOUNDED STIRRING LETTER FROM TROOPER TOM BROWN EXPERIENCES IN THE TRENCHES Mr Brown of Glass House Farm, Odd Down, has three sons in the North Somerset Yeomanry at the front. Troopers Gilbert, Tom and Harry Brown. The first-named is a grocer at Weston-super-Mare and he has been wounded in the knee. Mr Tom Brown, who is manager at Mrs Harrison’s Oldfield Bakery, has sent a very interesting letter to Miss Harrison, in which he says “Tell Mrs Gardiner not to worry about Fred; he is all right. There is no time for writing at present and he is feeling the strain of what we have seen and passed through. I’ll try and describe our experiences of last week. We arrived at ---------------- under shell fire. We were shelled all the time we were there. In the evening we went out to repulse a night attack made by the Germans. They retired and started shelling us with shrapnel. When we arrived back in the town we slept in underground cellars and took it in relays of two hours each guarding the horses during the night. OFFICERS QUARTERS HIT “During my relief, four shells fell quite near. One hit the officers’ quarters, after which we got orders to saddle up. So at 3.30 we moved and dug into trenches near the railway line some miles away. But the devils got our range again, so we retired about three miles. The next night we were ordered to the trenches. We have earned fame there, but, unfortunately, the price has been paid. We repulsed all the attacks with severe losses for them, while ours were comparatively slight. During one attack my rifle jammed, so I threw it down and picked up another. We gave them socks. During the afternoon of the next day we were ordered to take up our position in another trench and under heavy shell fire, which we successfully did. What we suffered with cold, rain and snow, open to all exposure, you can understand when I say we were in the trenches for 48 hours. Wilfy (Corporal Cross of Wellsway, Bath) and my brother Harry are safe, but Gilbert is wounded in the knee. We are resting at present. Lieut-Col Carr Glyn DSO, the commandant of the regiment, and Lieut G E Longrigg of Bath arrived in England on 72 hours’ leave. This would bear out the statement that the regiment was resting for some time. It is understood that several of the North Somersets are suffering acutely from rheumatism. TROOPER DAVIES OF BATH A postcard from the front to a Bathonian says that Trooper Davies [should be 'Davis'] of Bath was killed. He is a son of Mr Davies, newsagent, of Westmoreland Buildings, Lower Bristol Road, and joined the Yeomanry some six months ago. SHELLED BY THE GERMANS GRAPHIC LETTER FROM S.S.C. COX S.S.M. Cox of the Bath Squadron, who has been invalided from the front to a hospital at East Grimstead, suffering from an injured foot, writes to his wife as follows: I must tell you something of the poor old chaps who are going through it. I sincerely trust God in His wisdom will preserve my dear old chums whom I have left on the field of battle”. He then goes on to describe the regiment’s movements, saying: “We have marched and marched, lying nightly at all kinds of places until we came right to the front, to Ypres. We advanced along the line through Ypres, the town which is so frightfully ruined, and on under the shells of the enemy, but we got through safely. “CRASH AFTER CRASH” “Then we halted in close proximity to the large hospital of Ypres and we had just tied the horses round a field, when crash after crash came the German shells, bursting all round us, making holes in the ground large enough to bury a waggon and horses. We could not and dare not move the horses, and we were ordered to fall in for the trenches. A MIRACULOUS ESCAPE “We had only just formed up and moved away from the ground, when two of these large shells dropped on the very spot we had fallen in upon. We had only left the place five minutes, so we had a narrow escape. When I fell in for the trenches I was lame, but away we went over roads such as I had never seen before, all broken up by shells, a distance of about four miles to the fighting line. About half a mile from the trenches I dropped from exhaustion. One of the fellows helped me to a small hut and then we went and reported to Brigade headquarters. They at once sent a stretcher and took me to the field hospital.” ELEVEN HORSES BLOWN TO PIECES Before he was removed to the field hospital, Sergt-Major Cox learnt that eleven of the North Somerset’s horses had been blown to pieces – “amongst them my dear old mare”. ONLY 25 YARDS FROM THE GERMANS The severe nature of the attack which the North Somersets so gallantly repulsed can be well imagined from the statement which we have from a most authoritative source, that the Germans in daylight got to within 25 yards of the trenches which the Yeomen were defending so resolutely, but the North Somersets poured into them with such a withering rifle fire that they wavered, and those who were not wounded or killed fled before the repeated volleys. A NIGHT OF ADVENTURE LETTER FROM S.Q.M.S. CRAMOND Mrs Len Cramond was most relieved to receive a letter from her husband, S.Q.M.S. Len Cramond of the Bath Squadron a few days ago. It was written on Tuesday 17th and in it he says: “I am pretty well considering the horrible conditions under which we are existing. We are in the wilds and at present sleep in barns which let the rani through, and it is terribly cold. People at home don’t realise what the troops are going through. The roads here are terrible and we wade through mud the whole time. “Our regiment went into the trenches on Sunday night and are coming out tonight (Tuesday). A TERRIBLE FIGHT [Of the fighting, Cramond writes:] It was a

terrible fight. Our officers are fine. I would follow them anywhere but

unfortunately we have lost some of them, but it is such men as they who make

history. Remember me to all rifle, rowing and swimming and other friends and

chums. We want newspapers, notepaper and socks. I had to use my last pair to

clean my rifle.” |

| ||

| Bath Chronicle & Weekly Gazette 5th December 1914 contained this brief report of Alexander Davis’ death |

|

Alexander Davis appears to have fallen victim to German sniper fire. Whereas the advances of the Germans on foot were unsuccessful despite advancing in large numbers, other soldiers’ reports from the front line in this sector commented on the might of the German artillery and the considerable marksmanship of their snipers; the Germans were first to use this tactic of getting sharp shooters into positions to fire deadly rifle shots at individual targets. Further reports in the Bath newspaper on 5th December 1914 were based on other letters home, all of which corroborate the main facts of the North Somersets’ engagement, but each of which provides a few more details to paint a fuller picture of Alexander Davis’s last days: |

|

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette - 5 December 1914 LETTER FROM TROOPER S. STAPLEFORD“IT JUST RAINED SHRAPNEL AND LYDDITE” Mrs Stapleford of Prior Park Cottages has received a letter from her husband, Trooper S. Stapleford of the North Somerset Yeomanry. Writing on Nov 23rd he says: “We have had a very hot time since I wrote last. We were in the trenches for 48 hours and it was simply terrible. The German shell fire was awful. It just rained with shrapnel and lyddite. They made two determined attacks on us, but we drove them back each time. We lost about 68 men. Last Tuesday we were lying in some reserve trenches, resting, when we had orders to go into the front trenches, as they were in want of men badly. Out of the first ten that started only Jack Lilley and I got there. We never expected to come out alive. No words can describe the horror of it. We had to lie on three dead chums for eight hours. We were relieved by the 2nd Life Guards and then we went back to our billets, about seven miles. We left there for this place on Saturday and had to walk about 20 miles as the roads were too slippery for the horses to carry us; they kept falling down. I came down once and twisted my elbow. It does give me ‘jip’. I want some coloured handkerchiefs and chocolate and cake. We get plenty of tobacco, but are short of matches and cannot buy them. You need not worry about me. I may be home soon; there’s no knowing.” HOW THE PRUSSIAN GUARDS WERE DRIVEN BACK Trooper Pidsley of ‘A’ Squadron, North Somerset Yeomanry, who until the outbreak of war was employed by Mr W. G. Dickinson, jeweller, of New Bond Street, Bath, sends to his parents, who live at St David’s, Exeter, an interesting account of his experiences in the fighting at Ypres, Belgium. His letter is dated November 27th and is written from ‘somewhere in the North of France’. “We sailed from Southampton”, he writes “for Havre on the 2nd November and reached there on 3rd, resting just outside Havre under canvas for three days and then proceeded on a day’s journey by train. On arrival at the train terminus we moved seven miles out to a small village, where we stayed a week awaiting orders. Here we learnt that we had been attached to the 6th Cavalry Brigade. At three hours’ notice we started on a long trek to our comrades in Ypres – 40 miles roughly. The Germans were shelling the town heavily. SALVATION IN SOFT GROUND “In a railway cutting we had our first baptism of fire, a ‘Jack Johnson’ striking the bank and sending a shower of mud over a troop just in front of me. We tied up our horses in a field adjoining a military school in which we slept the night. While we were in this field, the huge shells were bursting all around us. Tremendous things; they make a hole in the ground 12 or 15 feet deep and about 20 feet wide. Mud and stones rained over us for about three hours, but we had miraculous luck; only one man being injured. The soft ground was our salvation, the shells burying themselves before exploding. At 8pm we moved out on foot towards the trenches as supports. After trudging three miles we were met by a General who told us we were not wanted. “BLOWN TO BLAZES” “When we returned we found that the square where the regiment had paraded had been blown to blazes two minutes after we left. More luck. Next morning we left our horses at a farm and started for the trenches. We did 48 hours in them. On the second day we were subjected to the most vicious artillery fire combined with infantry attack, the fiercest yet delivered at this point. Our regiment did splendidly and came out with honour. During the height of the battle the Prussian Guards advanced on our thin lines. They came in droves; huge fellows. Our boys were instructed to wait for them, and they did. At 100 yards we opened fire. ROUT OF THE GUARDS “The enemy stuck it for a minute or so and then turned, retreating anyhow. They were beaten. Our supports had come up, but our losses did not permit us to follow them up with the bayonet. During this time the French had left their trenches on our right before the German advance and retreated to a village. As is their custom, they rallied there and drove the enemy back with rifle and machine guns, the Germans suffering severe loss. The day closed with the honours ours. We had driven off the enemy, who outnumbered us by hundreds, including their finest Guards. We inflicted great losses on them; 375 were counted on the ground in front of our trenches. The Somerset boys’ casualties were just over 80, thirty being killed, the greatest percentage of these being from artillery fire and snipers” THE GERMAN SNIPERS He adds that the snipers are a special German Corps composed of crack shots specially trained to get near the trenches under cover and pot our officers and messengers. “They are devilishly successful and I am sorry to say accounted for a good few of our lads. I had good opportunity of studying their work, for being the Colonel’s orderly I was at all points, at all times, and I knew their presence too. A sergeant was sniped within a foot of me as we talked together in the reserve trenches at six in the morning. He went down smiling with a bullet clean in the centre of his forehead. General Allenbury has congratulated the regiment on its splendid work, and we are pleased. As for spirit we are as merry as little devils and in topping health.” |

| Other extracts from these letters include: |

|

TROOPER HOWARD

WALKER’S EXPERIENCES

A PERILOUS RUN "Four of us gained a little praise. We went to the support of our left wing, having to run across about 40 yards of open country under heavy fire. About ten started but only four reached the trenches. I don’t think I told you in my last letter that I had my hat hit off; a bullet going right through the top, and have been minus one since. Our troop got quite the worst of it, losing 12 men out of 20. I was the only one in our section in the trench who was not shot dead. "Did I tell you the Prussian Guard got within 20 yards of us? Of course you could not miss them. They reckoned our little regiment (about 120) accounted for between 600 and 700. I can assure you they looked more than that. The 3rd Dragoons, the 10th Hussars and the 3rd Life Guards were in our Brigade and were supporting us on the left flank and the French on the right. We all lost heavily and the Germans broke through the French lines, but were pushed back again at night. The trenches were about 200 yards apart, and our artillery were about one and a half miles back, supporting us grandly." |

|

The reference to the shot through the hat provides a

reminder that steel helmets were not issued to soldiers until well into 1915. |

Decoration | ||

| Trooper Alexander Davis would have been in receipt - posthumously - of the following medals: | ||

|  |  | ||

| 1914 Star with Mons bar | British War Medal 1914-18 | Allied Victory Medal |

|

The 1914 Star (with the words 'Aug' and 'Nov' on scrolls above and below the '1914' date) was only received by soldiers who served in France or Belgium before 23rd November 1914. These were effectively all men who had been serving with regular units of the army before war broke out, as these were the first to be sent on active service. The 1914 Star was known as the Mons Star because those who earned it were involved in the first phase of the war, which was the retreat from Mons. It was a real badge of honour, denoting those who had been among the very first to fight for their country. There was no question of having been conscripted, let alone late to join up The 'Mons bar' was added to the medals of soldiers who came under fire from the enemy in that period (rather than serving behind the lines). As far as we know, Alexander Davis was the only one of the South Twerton men to have earned the entitlement to the Mons bar, which adorns the ribbon. It cites the dates '5th August - 22nd November'. |

Commemoration | ||

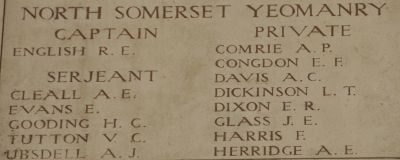

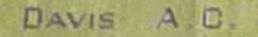

Trooper Alexander Davis is erroneously listed on the South Twerton School memorial as 'Private', and is also commemorated as follows: | ||

|

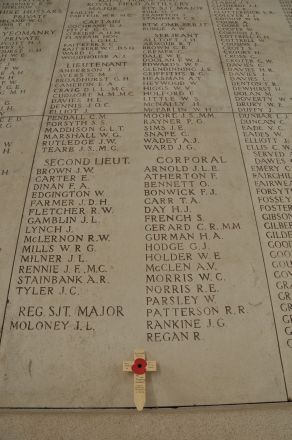

Menin Gate, Ypres The Menin Gate Memorial was built in 1927 on the site of an old town gate at Ypres – a site familiar to all who would have fought in this area – to commemorate 90,000 soldiers with no known graves who died in the battles in and around Ypres during the course of the war. Despite its size, the memorial was found to be too small and therefore contains ‘only’ 54,896 names; the remaining 34,984 (all killed after 15th August 1917, including the other South Twertonians Clifford Daymond & Charlie Edwards) are commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial. A ‘last post’ ceremony is still conducted every day at the Menin Gate memorial at 8pm. |

|  | ||

|

The Menin Gate Memorial at Ypres, which commemorates more than fifty thousand Allied soldiers who died in the fighting around Ypres and who had no known grave. | |||

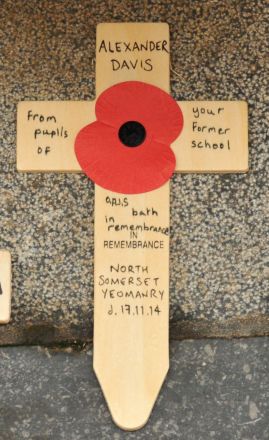

In June 2019, Bath resident Mike Sumsion visited the Menin Gate as part of his travels to the WW1 battlefields, cemeteries and memorials of the Western Front. He took with him the thoughts and remembrances of Oldfield Park Junior School pupils in the form of a wooden memorial cross, which was inscribed by pupils and taken by Mike to be placed beneath the inscription to Alexander Davis. Mike also kindly supplied the photograph of Alexander Davis's inscription (above) and the two photographs below:   | |||

|

Bath War Memorial See main page for details of the Bath War Memorial. Alexander Davis' inscription: |

|

|

East Twerton School Memorial Now called Oldfield Park Infants School (Dorset Close), the school WW1 memorial is in place on the wall of the school hall and includes a dedication to Alexander Davis: |

Further Information |

Living relativesIt would be great to hear from any living relatives of Alexander Davis. We know that his brother (Donald Gordon Davis) had a son (Gordon Donald, b 1931 in Bath) who seems to have died in 1982 without issue. We do not know what happened to Alexander’s elder sisters Mildred Kate Davis and Camilla Victoria Davis. Please get in touch!If you have any further information on Alexander Davis, or want to suggest corrections / improvements for this page, please use the Contact page to get in touch. |